|

TETLIN AS I KNEW IT

CHAPTER l

A Trip Around

Tetlin

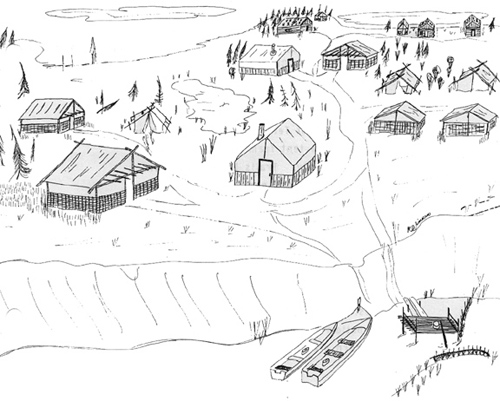

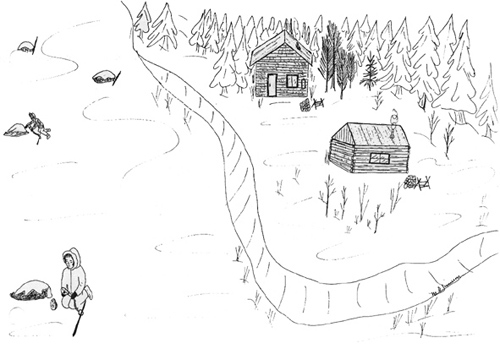

Let's imagine we're looking at the fish campsite -

Last Tetlin. From the riverbank, we can see a tent frame and a

smokehouse for each family. Trails branch out here and there from

the campsite. Fireweed is growing all over.

We walk to the back of the village. From there we

can see all the lakes - there are lots of them - which empty out

into the Last Tetlin River.

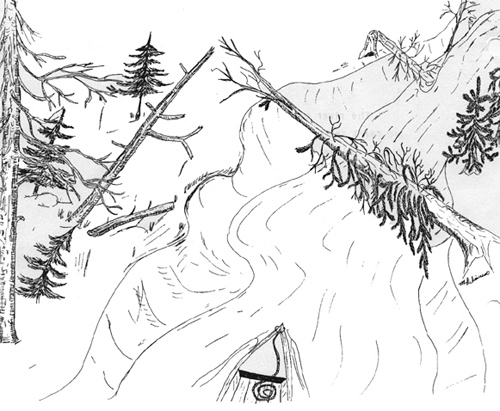

We take a boat downriver toward the fish traps. In

the clear spots we can look down to the bottom of the river and

see whitefish and northern pike swimming around.

The river curves, back and forth, so we can't see

very far down it from any one place. Along the banks there are

spruce trees and willows, and once in awhile we have to steer the

boat out of the way of a fallen tree that hangs over the river. As

we go down toward the mouth of the river, we can see that the

trees are getting taller and more dense.

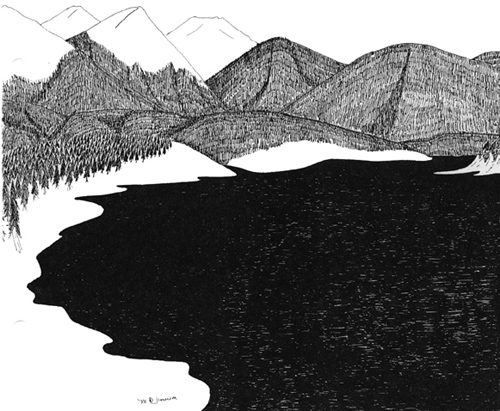

Last Tetlin River empties into Tetlin Lake - the

largest lake in the area. When we enter the lake from the river,

we see the mountains at the far side. They seem to flow into the

lake.

We'll go around the lake clockwise. The first creek

we come to is Bear Creek. It's very clear and ice cold, and there

are lots of fish in it in the summer and fall.

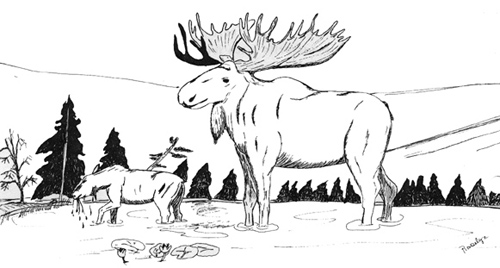

We go on past the creek, along the lake-shore, until

we come to an island. The lake between the Island and the shore is

very shallow and is a favorite place for moose. They feed on the

water lily roots.

All along the west side of the lake, there are

marshy areas like this where moose feed and ducks of all types can

be found.

Tetlin Lake is a major area for molting ducks in the

summer. Canvasbacks, widgeon, pintail, shovelars, greenwing teal,

and some mallards can be found there.

We'll go on to the north side of the lake. The land

becomes more hilly and the shores are rocky. This is one place

where my family fishes.

We'll keep going around the lakeshore. From the

northeast side of the lake we can see a hill we call "Rock Hill".

We pick raspberries on Rock Hill.

We go past Rock Hill, and the banks be-come high and

steep. We can't see much over the bank from our boat until we come

to the mouth of Tetlin River. Then we can see the area between the

mouth of Tetlin River and the mouth of Last Tetlin River; it's

flat and willowy.

(the canaries referred to are yellow

warblers).

Going up the Tetlin River, we can see only the high

banks for quite awhile. Once in awhile we can see bears up on the

banks -brown or black bears. Common snipes skitter along the

riverbanks. Blackbirds chatter. Woodpeckers hammer away somewhere

in the forest. We hear canaries, chickadees, and crows, all

singing or talking. How beautiful it all sounds!

Every now and then a creek empties water out of some

small lake into the Tetlin River. There are lots of willows -

river willows - hanging over the river.

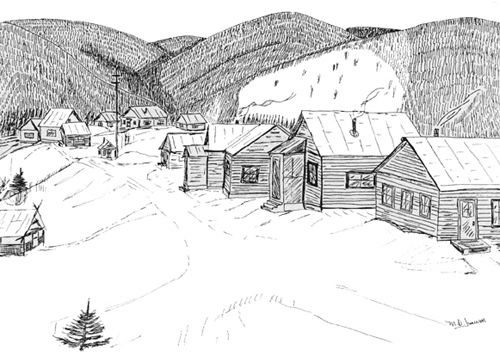

Finally we see Tetlin Village. It sits on the left

bank of the river, and we can see it clearly from the place where

we beach the boat. People come down to meet us - it doesn't matter

if we're strangers. They'll come down to meet us

anyway!

Before we go inside we take a look around. The land

rises from the village toward the north. One of the hills, called

Tetlin Hill, is a good place to find blueberries and cran-berries.

And to the south of the village, the land becomes marshy. That's

where the muskrat and beaver can be found.

From Tetlin Village we can follow a trail anywhere

we want to go - all over our land.

But that's a different journey!

CHAPTER II

GETTING READY FOR

WINTER

Fall was the time to get ready for the winter - the

start of another yearly cycle. There was lots to do.

When I was little, the women and children (and one

man, to protect us from bears) used to leave the village and go up

into the hills to pick berries. We picked cranberries,

bearberries, and rose hips. We'd be gone all day, and come back to

the village at night.

We dug roots, too - a kind called Indian potatoes.

They are very good when they're fried in moose grease.

Indian potatoes were obtained on the crest of the

hill between the river and the village on the winter trail to

Midway Lake. They're also called "Eskimo potatoes", and are the

species Hedysarum alpinum L.

Bears were not systematically hunted by Tetlin

residents. Berries were picked in the hills behind the village.

Blueberries were also picked there. The berry area is to the right

in photograph #2 of Tetlin.

Fall was also the time to do some last minute

fishing. We fished for whitefish and northern pike in the Tetlin

River close to the village, and we went up the Kalukna River for

grayling.

The men - my dad, brother, uncles, and some other

relatives - went hunting at Tetlin Lake. They stayed there until

they shot a moose. Then they cut it up and brought the meat and

hide back to the village.

Sometimes, if someone had a car or truck, the men

drove up the Taylor Highway to Mt. Fairplay to hunt caribou. In

the old days, my dad told me, they hunted caribou down by Last

Tetlin. There used to be a caribou fence there. But when I was

little, the men had to go all the way to Mt. Fairplay.

The meat, both moose meat and caribou meat, was

brought back to the village. There, the women dried it and smoked

it. The children had to keep a smoky fire going in the smokehouse

all the time. Besides smoking the meat, the fire kept the flies

out, too.

The women also tanned the hides. My mom used tanned

hides to make mittens, mukluks, and moccasins. She did beautiful

beadwork on the hides.

If we didn't do all these things -berry picking,

fishing, and hunting - our caches would be empty before the winter

was over. My mom and dad used to tell us that in the old days, an

empty cache meant sure death. So fall was a very important time of

the year for us.

Chapter III

Wintertime: Beaver

Camp

Both beaver meat and muskrat meat are eaten, dried

or cooked.

The trip took about 12 hours from 4a.m. till 4

p.m

In early February my family used to move to a beaver

camp called Sea Lake. We went by dog sled. My dad drove the first

sled packed with all our gear. He went ahead to break trail. Then

my mom followed, driving the second sled. This sled was packed

with us children.

At that time there were three of us: I sat in the

back, my brother Charles sat between my knees, and our baby sister

Betty sat in front of him. We were all wrapped up in sleeping bags

and canvas, and tied in with strong rope. We couldn't move at all,

we were tied so tightly. What a relief it was when Mom and Dad

finally decided it was time for tea break! It never came soon

enough for us.

When we got close to camp, my dad started setting

some of our beaver snares. Then when we got to the campsite, we

pitched the tent and started fixing it up. Dad put the stove in

place while Mom, my brother, and I gathered spruce boughs and

spread them on the tent floor. Dad got the fire going in the

stove, Mom cooked supper, and then we all went to bed early.

Tomorrow would be a busy day - we'd be setting the rest of the

snares.

Next day we got up early and ate a quick breakfast.

While Mom was packing lunch for all of us, Dad was hitching the

dogs to the sled. Then the whole family was off to set

snares.

Dad knew where he had set snares the year before,

and he went to those places to check out the old beaver houses.

Some-times beavers had abandoned their old houses and moved to new

ones. But sometimes the old houses were being used again this

year.

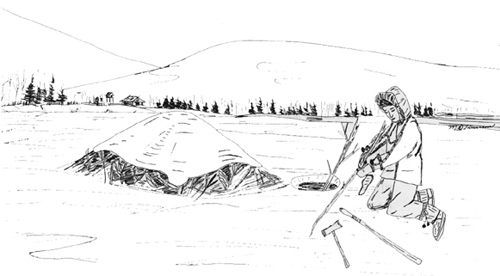

When we found a live house, Dad would chisel an

opening in the ice nearby. He cut a pole of fresh birch to use as

bait, and stuck it down into the opening he had made. By now the

beavers were tired of their stored birch, so they welcomed the

fresh pole my dad put down as bait. Then we looked for another

pole - a dry one this time - and put one or two snares on the end

of it. We didn't have to worry about the beavers eating the dry

pole. Dad lowered it down the hole next to the bait pole, kicked

some snow over the opening, and continued on to the next beaver

house.

We checked the beaver snares every day. On a good

day we'd come home with a load of beavers. Usually, after the

first day, just Dad and I or Dad and my brother would go along the

trapline, and the other three members of the family would wait

back at camp.

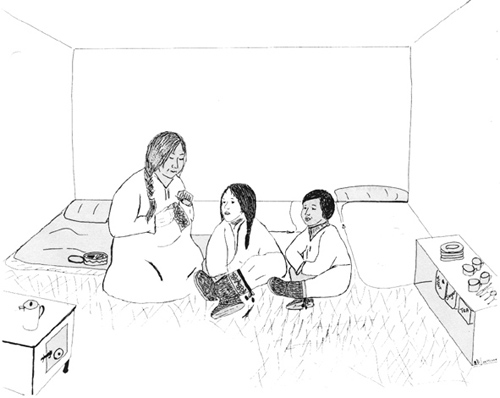

At night, Mom and Dad used to tell stories about the

days when they were growing up. Mom told us stories about how she

and her brother came to Tetlin to live with the chief after their

parents had died. Mom was only about 10 years old. She came from

Chena, and she had to learn a new language when she got to Tetlin.

She was often scared and lonely when she first moved to our

area.

Mom and Dad also remembered when white teachers and

ministers came to the Tetlin area, and how terrifying it was for

them. The people had to give up their old nomadic way of life and

settle down in one place. In order for their children to go to

school, they had to live near the school, and the children had to

learn English. People tried to make a living the new way -men

hunted for jobs, but jobs were scarce. This was a scary time for

the people of Tetlin.

When I think of the stories my parents told us at

beaver camp, I can still smell the fresh spruce boughs on the tent

floor, biscuits, tea, and the firewood in our tent. And I remember

lying in bed listening to the owls talk at night after everyone

else was asleep.

CHAPTER IV

SPRING AND MUSKRAT

TRAPPING

Sometime before break-up my family used to move by

dogteam to Dog Lake be-tween Tetlin and Northway for muskrat

trapping. We had a cabin there, so we didn't have to pack many

things - mostly some food and blankets. We joined another family,

the Tituses, who also had a cabin at Dog Lake.

Mom and Dad went out to set the musk-rat traps while

we children stayed around camp. The older children had to look

after the younger ones.

Sometimes we older children would go out on the

lake, find our own muskrat houses, and set traps in them. It's

easy to set traps. Just cut the top off the house and put a trap

inside in the ice entryway. Then put the cover back on the house,

and move on to the next muskrat house. We went back every day to

check the traps. We children used to get from 50 to 100 musk-rats

during one spring at muskrat camp.

Each of us skinned his own muskrats. We learned how

to stretch them and dry them, so we could sell them to the General

Store.

Around break-up time, when the snow became slushy,

we packed up our sleds and headed back to the village.

Even when we got back to Tetlin, we weren't yet

through with muskrats. We used to walk out to some of the lakes.

We'd take a dog with us who could retrieve and pack. Since the

lakes were open by now, we shot the muskrats with .22 rifles, and

sent the dogs out into the water to retrieve them. Once again, we

had to skin and dry our own muskrats. But we could keep the money

we got for the skins ourselves.

CHAPTER V

FISH CAMP AT LAST

TETLIN

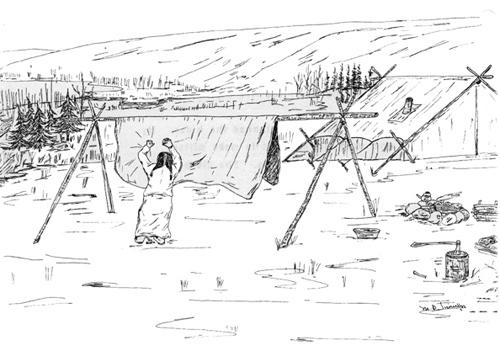

In late May, my family moved again. This time we

went to Last Tetlin by boat. By the time we got there, the

whitefish were running.

Almost the whole village moved to Last Tetlin in the

summer. Each family had its own campsite with a smokehouse. The

first thing everyone did was to fix up the tent and

smokehouse.

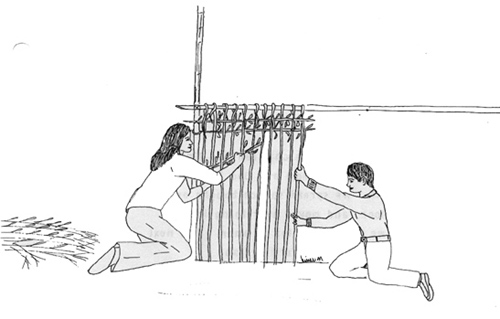

In our family, Mom and Dad put the tent up.

Meanwhile, it was up to the older children to repair the

smokehouse. We gathered long, thin willow sticks, and wove them

together into the wall of last year's smokehouse. We made the

walls pretty solid--solid enough to keep out dogs. We used the

smokehouse both as a place to eat and as a place to smoke fish

during the summer.

By the time we children had finished the smokehouse,

Mom and Dad had pitched the tent. We spread spruce boughs on the

tent floor, and moved everything inside. Then we were ready for

summer. The next day we would start cutting fish.

BLM planes came to Tetlin to pick up men for

firefighting whenever three was a fire.

Dad usually left camp to go firefighting with other

men from the village once we were settled in at Last Tetlin. So,

Mom took our family's turn at tending the camp fish trap and

caught all the fish we were going to need for the

winter.

There are two ways to cut up whitefish: ba' is for

eating and ts'ilakee is dog food. Mom prepared the ba', but she

let us children cut up fish for ts'ilakee.

We took the fish up to our family's campsite to

clean and smoke. Each fish cutter had his own fish cutting board

made of a split log. Mom and we children sat next to our cutting

boards and worked until all the fish had been cut. Then we could

go visiting around camp. We were always offered tea and fried fish

or fish stew.

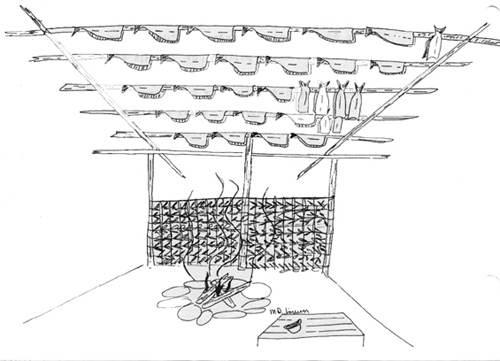

After a fish was properly cleaned and prepared, it

was hung up to dry on a pole in the smokehouse. My mother and

grand-mother kept a smoky fire going all the time. Besides smoking

the fish, they had to keep the flies out. A good, big rotten log

will burn all night with no tending.

Sometimes we dried the eggs along with the fish, and

sometimes we just fried the eggs and guts and ate them right away.

Dried fish eggs are better!

Birch bark was usually obtained in late May, behind

the village on the wooded hillside.

Once in awhile, when fish weren't running, the women

and children went berry picking. While Mom and Gramma picked, we

children sometimes trimmed the bark off a birch tree and scraped

up the sap with a knife. Delicious!

We stayed at fish camp until late July. Then we

packed everything up, went back to the village, and started the

yearly cycle over again, to prepare for the coming

winter.

|